Table of Contents

- Preface

- Where Rust is just better

- Rust's Shortcomings

- The Ecosystem

- Strictness can be a double-edged sword

- DSP in Rust

- Modern C++ isn't that bad

- The non-metallic elephant in the room

- Final thoughts

Preface

Rust vs C++, the age old debate. It's something I've been intimately struggling with this past year.

I used to be one of those "Rust evangelists" who would sing the praises of Rust and how it will deliver us from the evil that is C++. Now, Rust is still personally my favorite language, but the reasons are a bit different now.

I want to share my perspective on things, and maybe it will help others who are struggling with this or want to know what language they should learn.

Where Rust is just better

Let me start off on a positive note by listing some things which, in my experience, Rust is just plain better at.

The build system

Cargo is so nice. It makes managing dependencies and modularizing and structuring a codebase a breeze, and the fact that the same build system works on all platforms is a huge win (no meta-build systems like CMake).

The package manager

Having an official package manager like crates.io is just objectively better. I don't think this is a controversial statement.

Better memory safety

This one kind of goes without saying.

However, I do have some opinions on this which I'll get to later on in this article.

Syntax

Ok, this is more a matter of opinion. Rust's syntax can definitely take a while to get use to, but modern C++ can be a lot weirder IMO.

Friendly community

This is more important than you might think, especially if you're a beginner learning the language. The Rust community has gone out of its way to make sure it is friendly and inclusive. I've met people who said that Rust chat servers are a safe place for them (and yes I am partly referring to the furries and/or lgbtq+ people that seem to somehow be like a third of the makeup of these chat rooms. They're great people and I fully support them.)

Now this isn't to say that the Rust community is always a shining beacon of kindness, you of course have the occasional bad actor. But still I think these communities have done a good job of maintaining their status.

That being said, I've heard stories of C++ developers having a bad first impression of the community since some rustaceans are quick to criticize them for liking C++. Even if these people have good intentions, I think they are doing more harm to Rust's image than good. We need to keep in mind to respect other people's experiences on the subject.

Rust's Shortcomings

Now comes the part where I share my struggles with the language. I think it's important to look at things realistically, and I think evangelizing Rust as something that is better in every way might actually do more harm for the language than good. If we don't acknowledge the shortcomings, both new and experienced developers may end up hitting a brick wall of frustration.

The Ecosystem

This is a big one. Like really big. I think the Rust community tends to overstate the capabilities of the current ecosystem.

When it comes to writing capable software, features are key. Real-world software has a lot of nuance to it. You can't just assume that a pretty-looking minimalistic API will work for all use cases.

While this feature problem is most prevalent in the Rust GUI landscape, I've noticed it in other areas too. For instance, specifically for what I'm trying to do, I've struggled to find a cross-platform library for proper low-latency connections to system audio and MIDI devices.

Let me tell you, when a Rust library works great for your use case, it's amazing. But when it doesn't, it sucks.

To put this in perspective, it's important to keep in mind just how vast the C++ ecosystem is. There are so many solutions available. It becomes disheartening to learn that a C or C++ library already does what you want, but Rust doesn't have one.

The Solution

There is a way around this issue, and that is to use bindings to existing C or C++ libraries.

When you first learn Rust and how great it can be, it becomes all too easy to want "Rust purism", where you only depend on libraries that are written in Rust. However, I've come to learn that if you wish to make production-ready software in Rust, you shouldn't shy away from the idea of using bindings to mature C/C++ libraries.

There is so much time and effort that has gone into these mature libraries. Sure they aren't perfect, but they can help you get the job done.

I recently created my own Rust bindings to RtAudio called rtaudio-sys, as well as a safe and easy-to-use wrapper around it called RtAudio-rs. It took a while to learn how to do, and there were some headaches along the way. But if and when I have to do it again, I'll be more comfortable with it.

That being said, I don't recommend trying to create your own Rust bindings to a library if you're new to Rust. You need to learn how Rust build scripts work, and you also need some experience and knowledge in creating safe wrappers around unsafe FFI code.

So my word of advice is: if you are thinking about using Rust for your project, unless you are willing to fill in the gaps yourself, make sure that Rust libraries can actually do what you want first. For a lot of use cases, I think the answer is actually yes, the Rust ecosystem is able to do what you want. But for other use cases the answer may be no. And even then, you need to be okay with sometimes relying on younger experimental libraries rather than mature and battle-tested ones.

Obviously the C and C++ ecosystem has had a lot more time and money thrown into it. Perhaps one day Rust will truly catch up, but pretending it's already there is being unrealistic.

Strictness can be a double-edged sword

Rust is very strict in what you can and can't do, and that is of course by design. Computers are inherently unsafe machines, and it takes a lot to prevent developers from messing up.

One of Rust's defining features is that it forces you to design your code architecture in a memory-safe, less error-prone way. And when you do need to use unsafe features, you can wrap the unsafe parts in a safe abstraction that can't be misused. In most cases, this works wonderfully.

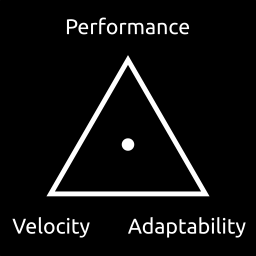

But I do think there's an important "limit" to this tradeoff that should be considered. If you remember my previous post DAW Frontend Development Struggles, I presented the idea of the "performance, velocity, and adaptability" triangle (and in this context, you can interchange "adaptability" with "abstractions").

There comes a point where having to deal with safe abstractions and "less error prone" code architectures really feels like it's more effort than it's worth. Sometimes it even comes at the cost of performance as well (the Rust GUI ecosystem is one the best examples of this). It's important that we acknowledge these frustrations. Pretending like it's not a problem is only going to deter people away.

There's a common pattern I see all too often in Rust code, which I call a "pointer with extra steps". It's when you have integer "IDs" that are used to index into an vector or a hashmap. This essentially recreates the functionality of a pointer without having Rust's compiler complain at you. While sometimes this makes sense, other times it's a roundabout way of doing things and the performance can actually be slower than if you just used the

Rc<RefCell<T>>smart pointer in Rust (indexing requires an extra multiply and add operation, and a hashmap requires even more steps). And if you are creating a custom data structure,Rc<UnsafeCell<T>>(or even raw pointers) would be even faster. But of course sinceRc<RefCell<T>>is cumbersome to type and indexing into a vector or a hashmap is not, people tend to choose the latter.Although there is a situation where indexing with integer IDs can make more sense, and that's when you are iterating multiple elements at a time in a (not too large) vector. Because the elements are laid out in contiguous memory, if the size of the Vec in bytes is small enough to fit inside the CPU's cache, then this can actually be faster than dereferencing multiple smart pointers.

Another valid use case for indexing into a vector is when you need a pointer in one thread that references owned mutable data in another thread (because

Arc<Mutex<T>>can be slower). Though when it comes to hashmaps, I'm not sure whether theArc<Mutex<T>>smart pointer is faster or if the FNV hashmap is faster. My gut instinct says the former should be faster, but I haven't measured it.Edit: some corrections

I've experienced this first-hand when creating my DAW engine. It gets tempting to just throw in UnsafeCells and unsafe functions in places.

Sadly though, I don't have a real solution to this problem, aside from just encouraging crate developers to create more solutions that can cover more and more use cases. Don't provide just one way of doing things in an API for the sake of "prettiness", provide multiple ways to use the library to better fit with more use cases. Don't shy away from traditional concepts the require "uglier" APIs.

And for non-crate developers, you shouldn't be afraid to resort to unsafe Rust if your use case really does call for it. If you aren't creating a library for others to use, and creating safe abstractions is too much work, try just putting a comment saying exactly what you can and can't do with a function (and mark that function as unsafe). As long as your codebase isn't too large and complicated, this kind of old-school global reasoning can be effective.

DSP in Rust

There's another area where I've found Rust's rules to be a slightly more of a hinderance than a help, and that is with actual DSP processing code. (This is definitely a minor issue that can be worked around, but I think it's still worth mentioning.)

DSP code needs to fast. A single gain operation on a stereo signal at 48,000 samples a second requires 96,000 multiply operations. Any additional runtime memory-safety checks like bounds checking an array index will really add up.

The Rust compiler needs to be absolutely sure that things are sound before removing those runtime checks for you. Now while it's great at optimizing simple DSP algorithms, I found it can struggle with more complicated real-world DSP pipelines. If you really care about performance, you need to check the assembly output to make sure it is doing what you want, and if it's not, add some additional code to try and coerce it into realizing that it's safe. (And also make sure that a future compiler update doesn't break it.)

You can of course use unsafe Rust to get around this issue, but IMO that kind of defeats the purpose of using Rust for DSP in the first place. (However, in the context of making audio plugins, I do think Rust still helps with all of the plumbing involved, especially with libraries like nih-plug.)

And if you want to use SIMD intrinsics (and you should if you're serious about DSP), you need to use unsafe anyway. This is because the SIMD functions in Rust are marked unsafe since they can cause undefined behavior if the code is ran on the wrong processor. There is an official solution to this in the works called portable-simd, but it's still only available on the less-stable nightly compiler.

And yes, auto-vectorization is a thing, but again it can be unreliable for more complicated DSP pipelines.

There's also the problem I have with the fact that because I want to use a lot of existing open source DSP in my projects, I would have to spend extra time translating that DSP code from C++ to Rust. It's yet another tradeoff that made me once consider switching to C++.

Modern C++ isn't that bad

Yes, Rust is still better, but I do think modern idiomatic C++ gets a bad rap.

C++ isn't standing still, it's always adding better and safer features. Now of course it has the problem of not depreciating old features and legacy codebases, but I think the point still stands. If you become proficient with modern idiomatic C++ and good code architecture, I believe you can go a long ways without too many issues. Adding to this, modern linters and other static analyzer tools are there to help provide some guardrails.

Here are some additional tools I found can help make you life easier with C++:

- CPM - Dependency management tools for CMake

- Catch2 - C++ unit testing framework

- {fmt} - A modern string formatting library (especially useful for debugging and logging)

- Infer, Flylint - Linting and static analysis tools

- sanitizers - A list of memory sanitizers

- OSS-Fuzz, libFuzzer, AFL++, Honggfuzz - Fuzzing tools

However, there is something to be said if you are working with a team of developers on a larger project. It's hard to enforce everyone to use modern features, practices, and tools. And on top of that, miscommunications can still lead to a lot of problems.

This is where I think Rust truly shines. The strict type system, borrow checker, and compiler-enforced rules are proving to be invaluable for large software projects. It's no wonder large companies like Microsoft are planning to adopt Rust for some of its systems.

The non-metallic elephant in the room

And lastly, there's Carbon on the horizon. A C++-compatible language with a cleaner syntax and a memory-safe subset seems like a killer solution. If it's successful, it might just well be the language that supersedes C++.

But it's still quite a ways from being production-ready, so who knows?

Even then, I think it's daft to think that Carbon will replace Rust someday. Carbon is meant to be a transitional solution, with languages like Rust, Go, Swift, and Kotlin still being a better option if you have the luxury of not maintaining a legacy C++ codebase.

Final thoughts

C++ is definitely messy, but so is the real world. I've come to learn that it's just another tool, and if someone prefers it, then they shouldn't be berated for using it. (The same can be said for C, although I do think maintaining a large codebase in C is much harder.)

And for me personally, there's one main reason I'm choosing to stick with Rust: I'm just used to it now. I've become really proficient with it, and it would take a lot of work to reach that same level of proficiency in C++. In the end, that's the ultimate goal of a programming language, to allow you to create the software you want as quickly and easily as possible.